5 Introduction to Environmental DNA

5.0.1 What is environmental DNA?

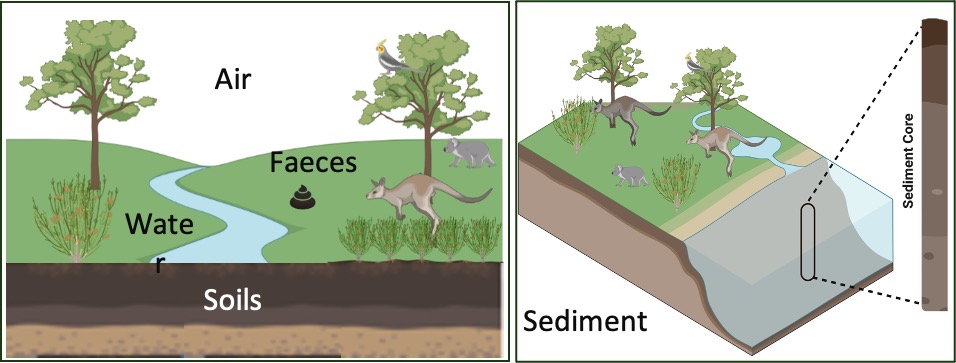

DNA can be recovered from virtually anywhere. In fact, DNA can be found in the environment from cellular material shed by organisms (e.g., skin flakes, urine, faeces, hair, mucus, or their natural demise) that have accumulated in the surrounding water, soil, air, sediment (Figure 5.1). We call this type of DNA, environmental (eDNA).

Environmental DNA (eDNA) refers to the genetic material that can be extracted and studied from environmental samples without the need to isolate target organism first (Taberlet et al. 2018).

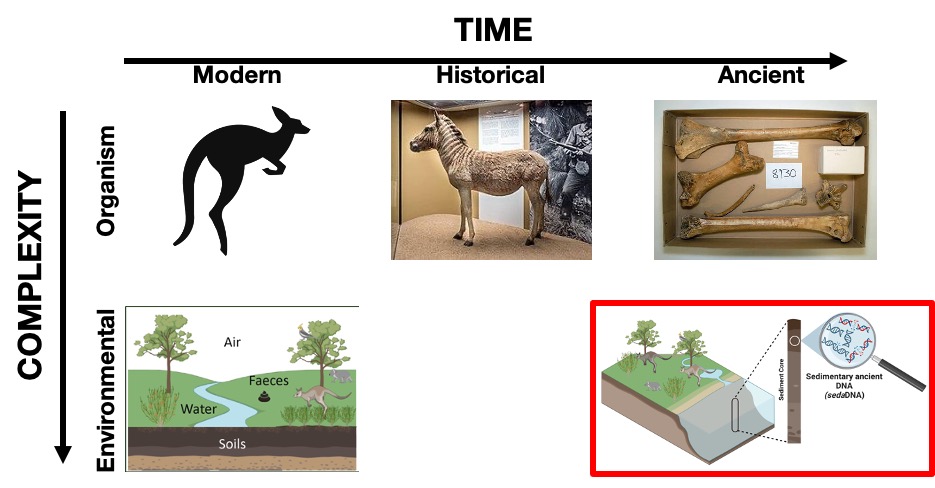

A defining feature of eDNA is its complexity. In environmental samples, we encounter a diverse mix of genetic material from multiple species and individuals, presenting unique challenges in the analysis compared to the analysis of genetic material of a single organism (Figure 5.2). Additionally, in some environmental substrates, DNA from certain organisms can be preserved for long periods even after the organisms have died. This preserved DNA is referred to as ancient eDNA (Pedersen et al. 2015).

Introducing the element of time to the already complex eDNA scenario further intensifies its complexity. Time can be unkind to DNA, and the deeper we venture into the past, the more challenging it becomes to recover intact genetic material (Figure 5.3). Ancient environmental DNA embodies the intertwining challenges of temporal degradation and environmental complexity. Consequently, the earliest studies in this field have emerged recently in the early 2000s, only two decades ago (Coolen and Overmann 1998; Willerslev et al. 2003).

Over the past decade, there has been a growing interest in researching ancient eDNA, particularly the DNA present in sedimentary archives (E. Capo, Barouillet, and Smol 2023).Sedimentary DNA can be well-preserved in freshwater and marine sediments, palaeo-soils, caves and permafrost. This preservation is facilitated by oxygen-depleted and cold sediments in aquatic environments, as well as the sheltered conditions provided by caves, which can offer relatively stable temperature and humidity (E. Capo, Barouillet, and Smol 2023). These preservation conditions allows for significant potential in reconstructing past environments and tracking ecological changes over time (Kjær et al. 2022).

5.1 What can we find in sedimentary DNA records?

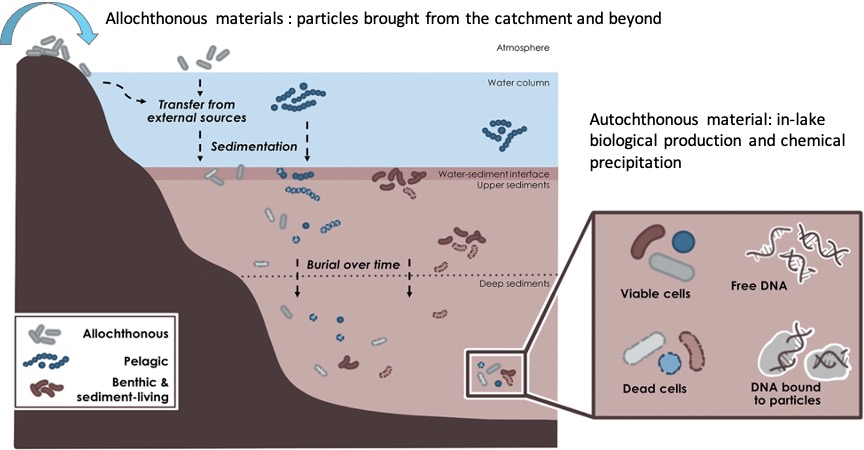

Sediments consist of inorganic and organic matter, including eDNA, that accumulate over time, creating temporally resolved archives (Picard et al. 2024). The vertical stratigraphy of these sediments allows for the reconstruction of temporal transects through the sediment core. In aquatic environments, the sedimentary DNA record comprises a mixture of genetic materials from organisms that live within the lake (autochthonous material) and those from the surrounding area and its catchment (allochthonous material) (Eric Capo et al. 2022). In terrestrial enviroments like caves, the sources of DNA that form the sedimentary record are different. Caves can act as natural traps where organisms repeatedly fall in and perish, or as places of refuge where organisms seek shelter (Murchie et al. 2023). Consequently, the sedimentary records in caves can include genetic material from these organisms. Additionally, microorganisms can live within cave sediments, integrating their genetic material into the sedimentary DNA record, similar to aquatic environments.

The pool of DNA preserved within sediments can be categorised into two primary fractions (Eric Capo et al. 2022) (Figure 5.3):

- Ancient molecules: This category comprises DNA found within dead cells or as extracellular DNA, either in its free from or attached to particles

- DNA within viable or living cells: This includes DNA in cysts, spores, pollen, and eggs These cells may be actively growing within the sediments or in a dormant state, capable of reactivation under favourable environmental conditions

Therefore, (Eric Capo et al. 2021) defined the two distinct fractions of DNA found in sediment based on their degradation states as:

- Sedimentary DNA (sedDNA): includes DNA that is relatively young and better preserved

- Sedimentary ancient DNA (sedaDNA): comprises older DNA that tends to be more poorly preserved

5.2 Taphonomic processes of sedimentary DNA

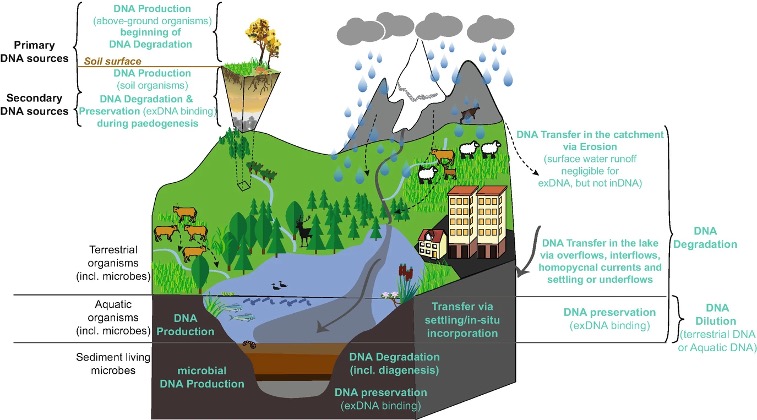

The reliability of DNA records is influenced by taphonomic processes (Sand et al. 2024; Giguet-Covex et al. 2023). Taphonomic processes refer to the various mechanisms that regulate the production, transfer, incorporation, and preservation of sedimentary DNA. In this section, we will focus on aquatic environments (Figure 5.4), but similar processes can also affect sediment records in caves.

5.2.1 Origin of eDNA in sediments

Several factors come into play in determining how DNA is incorporated and buried within the sediments (Giguet-Covex et al. 2023). These include the abundance and spatial distributio of organisms, their ability to form cysts or spores, and their edibility (Eric Capo et al. 2021). For terrestrial species living in the surrounding area of aquatic environments, understanding material and DNA transport from the original habitat is essential to ensure reliable interpretation of the genomic records. For example, more terrestrial plant DNA is expected to be transported to lakes with high soil erosion and well developed hydrological connections (Garcés-Pastor et al. 2023).

5.2.2 Fate of eDNA in the environment

Upon release into the environment, DNA molecules can undergo various processes (Torti, Lever, and Jørgensen 2015).

- Biotic degradation: Extracellular DNA becomes susceptible to extracellular and cell-associated DNases, which are likely the most immediate cause of DNA degradation (Torti, Lever, and Jørgensen 2015). These enzymes are widespread in most environments and catalyse the hydrolysis of the phosphodiester bond between the phosphate and the deoxyribose moieties of DNA.

- Natural transformation: Living cells can take up extracellular DNA molecules from the environment, even if the DNA is extensively damaged, and integrate them into their own genomes (Overballe-Petersen et al. 2013).

- Abiotic decay: As you already saw in the ancient DNA lecture, DNA repair mechanisms cease to be active, and DNA will start accumulating lesions inflicted by various abiotic (physical and chemical) factors (Orlando et al. 2021).

- Long-term preservation in the environment: Despite the occurrence of the previous processes, extracellular DNA can still persist in the environment. Optimal DNA preservation conditions in aquatic environments include systems with cooler temperatures, lakes with minimal bioturbation, anoxic conditions at the sediment-water interface, and freshwater and neutral to slightly alkaline lakes (pH 7-9) (Jia et al. 2022). DNA can be protected from nucleases by binding to humic acids due to a negative surface charge, and therefore prolong DNA survival (Stotzky 2000). DNA is also protected from degradation upon adsorption onto mineral grains in the sediment matrix, which reduces DNA accessibility to nucleases. This adsorption process is crucial for preserving DNA molecules in sediments for millennia.

Let’s delve deeper into this preservation process.

5.2.3 Mineralogical influence on preservation

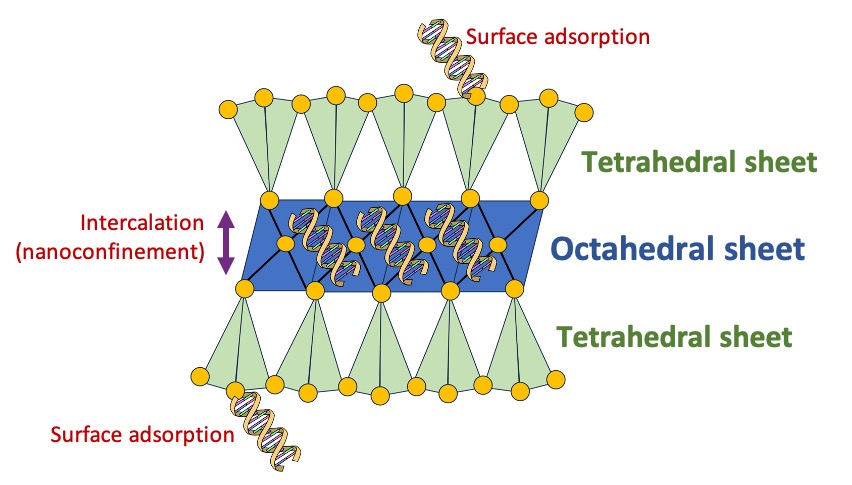

Different minerals have varying adsorption capacities, yet research has demonstrated that specific clays appear to be the most effective at preserving eDNA compared to other common soil and sediment silicates (Lorenz, Aardema, and Krumbein 1981; Kjær et al. 2022). For example, clay minerals such as montmorillonite (belonging to smectite clays) can absorb more than their own weight in DNA, because of their relatively large negatively charged surface area (Pedersen et al. 2015). Compared with clays, sand has been found less effective in binding DNA, but adsorption increases with divalent cation concentrations (Ca2+ and Mg2+) (Lorenz and Wackernagel 1987). We can use this information to target layers in sediment records that have high clay content as hotspots for ancient eDNA (Kanbar et al. 2020).

How do they work? Let’s take smectite clay as an example (Figure 5.5). Smectite clays belongs to the 2:1 clay type, characterised by two tetrahedral layers surrounding an octahedral layer. In the case of smectites, the middle octahedral layer contains a variable cation content. When spaces become available, a charge is generated. This charge allows both organic and inorganic compounds to intercalate into this layer, effectively ‘nano-confining’ and shielding the DNA from the various factors that might otherwise cause its degradation over time, such as nucleases. These nucleases can themselves adsorb to sand and clay, potentially inhibiting their ability to hydrolyse extracellular DNA (Beall et al. 2009).

5.3 DNA analysis: laboratory processing

The reliability of DNA records is influenced not only by taphonomic processes but also methodological aspects. As with any aDNA study, all laboratory processes must be conducted in specialised aDNA facilities, adhering to strict aDNA protocols when handling samples, as covered in previous lectures.

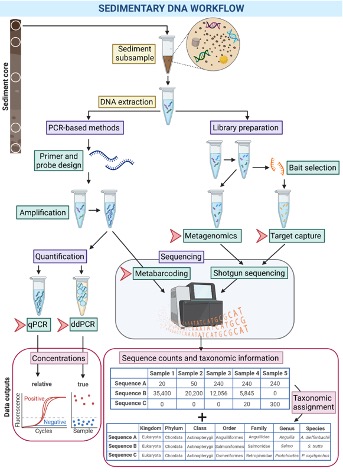

Once the sediment sample has been collected, the first laboratory processing step involves DNA extraction (Heintzman et al. 2023; Picard et al. 2024) (Figure 5.6). This process involves isolating and purifying DNA from various biological samples and separating it from other cellular or environmental components.

DNA extraction methods can vary depending on the DNA source and the specific downstream applications. In the field of eDNA and therefore, sedimentary DNA, the choice of DNA extraction method can significantly impact the resulting DNA composition. Some methods may fail to recover a significant number of DNA molecules from a sediment sample, affecting the accuracy of the reconstruction of the genetic record (Eric Capo et al. 2021).

A wide range of methods have been used in sedimentary DNA research, ranging from commercial kits (e.g., Powersoil® and PowerMax® from Qiagen) to custom protocols optimised for recovering short DNA fragments, a characteristic feature of ancient DNA (Epp, Zimmermann, and Stoof-Leichsenring 2019). Studies comparing different extraction methods have emphasised the importance of selecting methods optimised for different sediment types and taxonomic targets (e.g., Slon et al. 2017; Armbrecht et al. 2020; Murchie et al. 2021; Pérez et al. 2022).

After extracting eDNA, various analytical methods have been used to analyse the DNA (Heintzman et al. 2023; Picard et al. 2024). These methods encompass the following approaches:

- Techniques designed to detect or quantify specific target organisms using endpoint PCR assays, quantitative real-time qPCR, and specialised applications like droplet digital ddPCR.

- DNA metabarcoding methods that involve PCR amplification of marker loci, often referred to as “barcodes,” coupled with high-throughput sequencing.

- Metagenomic strategies centred on untargeted shotgun sequencing of the entire pool of DNA retrieved from sediment.

- Hybridization-based target enrichment methods for the recovery of DNA fragments of interest from the sediment metagenome. Hybridization capture involves the use of short DNA or RNA probes, often referred to as “baits,” which are designed to complement specific DNA sequences of interest, such as taxonomic marker genes. These baits can then be employed to selectively extract the target DNA fragments from the DNA extract for subsequent sequencing.

Recovered DNA sequences are then taxonomically and/or functionally annotated using a suite of bioinformatic tools to answer palaeoecological questions.

5.4 Precautions and considerations in ancient eDNA research

While the application of ancient eDNA may appear promising, it is, in fact, quite challenging. There are numerous precautions and considerations that must be taken into account when conducting this type of research to accurately reconstruct past biological communities.

5.4.1 Contamination control in field and laboratory sampling

Contamination control measures begin at the sample collection stage (Rawlence et al. 2014). Sampling must follow rigorous protocols, which include the use of protective gear such as gloves, facemasks, or full-body suits, and the utilization of sterilised equipment (Figure 5.7).

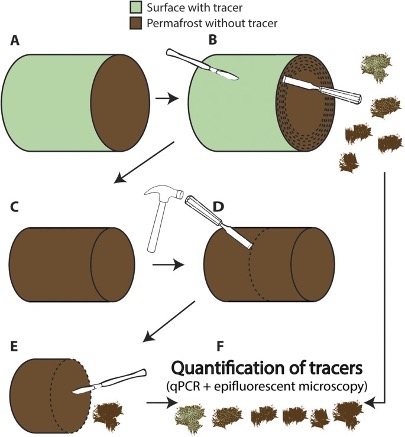

5.4.2 Tracking contaminants in field sampling

In coring procedures, a visible chemical (e.g., perfluoromethyldecalin, PFMD) or DNA-based tracer can be applied to the sediment core to assess the extent to which potential external contamination infiltrates the extracted core (Figure 5.8). The tracer can be applied to the surface of the core before sampling, or it can be applied during core retrieval in the field. After applying the tracer, the core surface is removed, and the sample is collected (Epp, Zimmermann, and Stoof-Leichsenring 2019). The presence of the tracer DNA on both the removed surface and the collected samples is then verified using PCR or qPCR (Bang-Andreasen et al. 2017).

5.4.3 Taxonomic assignment and community reconstruction

One crucial factor when creating lists of species from DNA sequences found in sediment is having good reference databases. If these databases are not comprehensive and meticulously maintained, you may miss the identification of certain species in your samples. Some databases may even contain errors, like contaminants or wrongly identified sequences, which could lead to incorrect results (Cribdon et al. 2020).

Another essential consideration is the analysis process, known as the bioinformatic pipeline. This includes the specific software tools and steps used to turn your DNA sequences into a list of species and their quantities. Setting the right parameters and thresholds in this pipeline is crucial for accurate results. So, to generate reliable species lists from sediment DNA data, you need both a solid reference database and a well-designed analysis pipeline (Cribdon et al. 2020).

A good example, though from a modern metagenomic study, is the widely reported metagenomic analysis of the New York subway, which initially suggested that pathogens like Yersinia pestis and Bacillus anthracis were part of the “normal subway microbiome” (Afshinnekoo et al. 2015). However, subsequent reanalysis using more appropriate methods did not detect these pathogens (Ackelsberg et al. 2015). Commonly used software pipelines can produce results that lack prima facie validity (e.g., reporting widespread distribution of notorious endemic species) but appropriate use of inclusion and exclusion sets can avoid this issue.

5.4.4 Spatial heterogeneity of sedaDNA

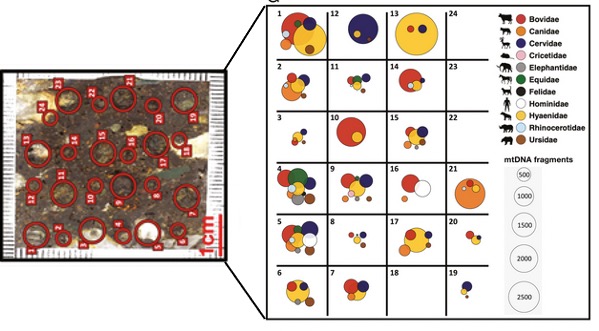

Spatial distribution patterns of eDNA can be strongly heterogenous within sediments even at a microscale. For instance, eDNA from animals may originate not only from microscopic bone and teeth fragments but also from extracellular DNA present in bodily fluids or as a result of tissue decomposition. This distribution can be uneven across different sections of a sedimentary profile.

A study conducted by Massillani and colleagues in 2021 (Figure 5.9) illustrated the varying taxonomic compositions of mammalian mitochondrial DNA on a microscale within resin-impregnated archaeological sediment blocks collected from prehistoric sites in Europe, Asia, Africa, and North America (Massilani et al. (2022)). Their findings highlighted that DNA may be concentrated in specific sources such as bone and coprolites within the sediments.

Researchers should consider this factor when designing studies based on sedaDNA, particularly during the sample collection phase. Neglecting this heterogeneity could potentially lead to false negative results, especially for rare species. Modifying the number of sampling locations and increasing natural replicates per location in the study design could enhance the reliability of species detection.

5.4.5 Vertical migration of DNA

Another challenge associated with the sedaDNA approach, especially in non-frozen environments such as cave sediment records, is the potential risk of DNA moving vertically between different layers (DNA leaching) and contaminate lower (older) layers.

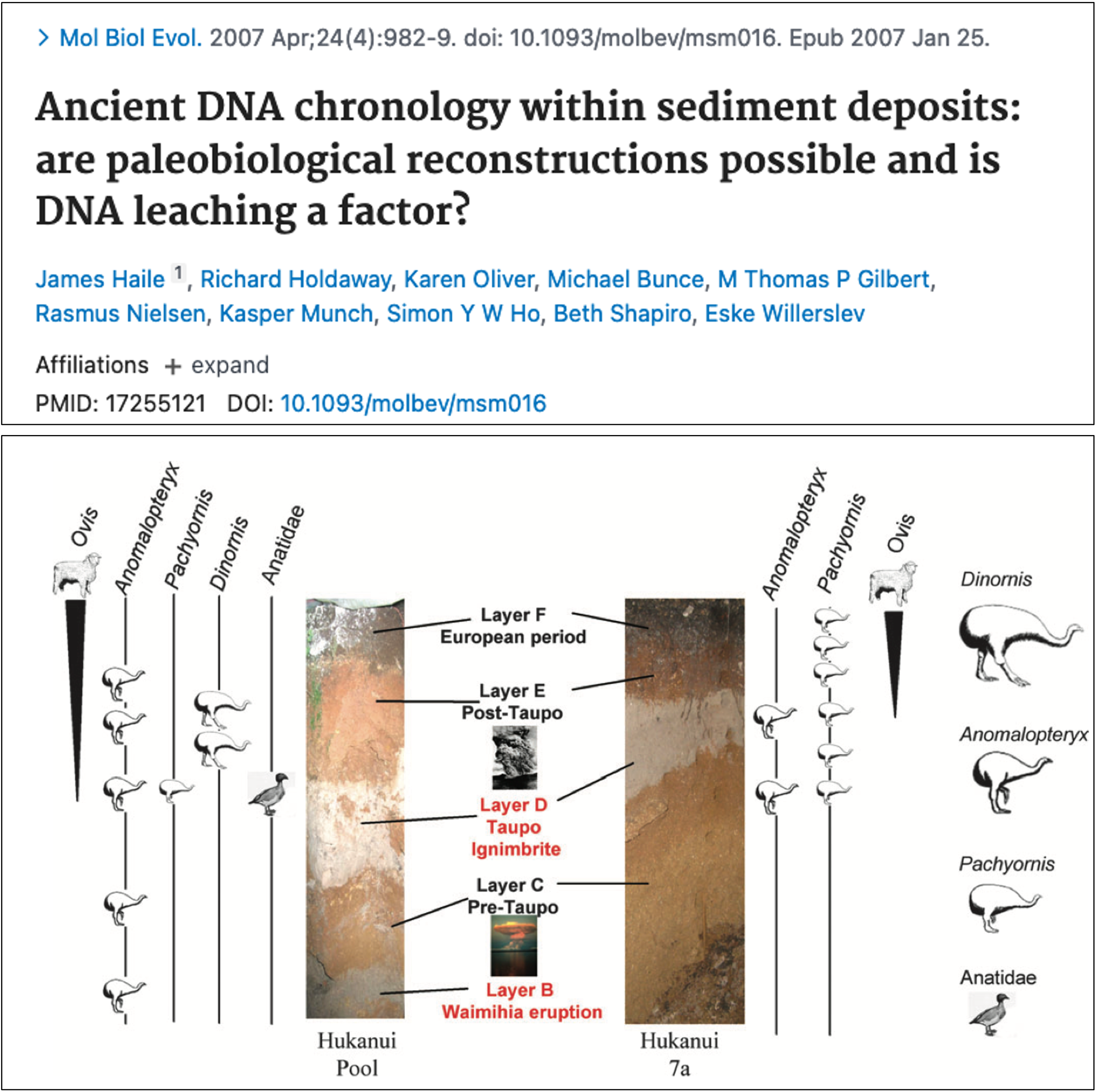

To investigate this issue, Haile and colleagues (2007) extracted aDNA from sediments up to 3300 years old at two cave sites on New Zealand’s North Island (Figure 5.10). These sites offered a valuable opportunity to study vertical DNA migration, as the sediment layers spanned both pre- and post-European periods. This allowed them to test for the presence of non-native species, such as sheep, in sediments deposited before European settlement, providing an indicator of DNA movement within the strata. Their findings revealed that sheep DNA was found alongside moa DNA, an indigenous species, in pre-European strata, suggesting that genetic material had migrated downward through the sediment (Figure 5.10). However, the amount of sheep DNA reduced as sediment age increased. This research highlighted the potential of sedimentary DNA as a valuable resource for understanding past environments but also suggested that considerable caution should be taken when interpreting DNA profiles from sediment records.

Downward infiltration of water can transport DNA through the porous, granular sediments of caves and potentially soil profiles (Haile et al. 2007; Jenkins et al. 2012). However, other studies indicate that this phenomenon is less likely in lake sediments or permanently frozen sediments. Once lake sediments are compacted, vertical pore water movement is minimal, leading to the immobilization of multivalent metals and organic compounds in the sediment matrix (Anderson-Carpenter et al. 2011).

5.4.6 Potential applications

The use of ancient environmental DNA has enabled the reconstruction of palaeoenvironments, facilitating the detection of hominins and the study of biotic turnovers in ecosystems. This has also provided insights into ecosystem restoration targets.

Classical paleoecology has explored biotic responses to environmental change but often fails to capture the full diversity of organisms, their co-occurrences, and interactions. Sedimentary ancient DNA provides an opportunity to address this gap by potentially reconstructing ecosystem diversity examining all domains of life at a certain point in time. However, integrating traditional proxies into the studies, such as pollen and fossil analyses and archaeological evidence, remains essential, as each proxy provides complementary information, often with minimal overlap. Each method is influenced differently by factors such as differences in biomass production, distance from source to deposition, and preservation conditions. A combination of DNA and traditional proxies leads to a more robust interpretation of the results.

For example, in a study by (Parducci et al. 2019), past vegetational communities were reconstructed from lake sediments in southern Sweden over the last 15,000 years using shotgun metagenomic analysis of sedimentary DNA alongside pollen and plant macrofossil analyses. Each proxy provided unique insights: pollen revealed information about both local and regional vegetation, plant macrofossils reflected local vegetational communities, and eDNA provided strong signals about local plant communities. By comparing these proxies, the researchers were able to distinguish plants growing within or close to the lake from those present in the broader region. Notably, sedaDNA offered a more robust indication of changes in plant communities compared to the other traditional proxies.

5.4.7 Palaeoenvironmental reconstruction

A good example of this type of this application is the study published by (Kjær et al. 2022). The Late Pliocene and Early Pleistocene epochs (3.6 to 0.8 million years ago) exhibited climates resembling future warming predictions. However, knowledge of the biological communities in the Arctic during this period remains limited due to the scarcity of fossils. In this study, the authors recovered ancient DNA from permafrost sediment samples in North Greenland, unveiling a diverse ecosystem that included an open boreal forest, various vegetation types, and a wide range of animals such as mastodons, reindeer, rodents, and geese. The presence of certain marine species (e.g., horseshow crab and green algae) suggests a warmer climate compared to the present. This use of ancient eDNA and traditional palaeoecological proxies (e.g., pollen) opened up new avenues for tracing the ecology and evolution of biological communities dating back two million years (a new record in the aDNA field!). The long-term preservation of this ancient eDNA is most likely attributed to its binding to mineral surfaces.

5.5 Insights provided by microbial shifts over time

Understanding how microbial diversity and function change over time and space is crucial for comprehending how ecosystems respond to global changes. Microorganisms, particularly prokaryotes, play essential roles in ecosystems by facilitating biogeochemical cycles and they are also the fastest responders to environmental changes. However, prokaryotes have been overlooked in long-term ancient eDNA studies due to the difficulty in determining whether their DNA signals originate from sediment-living organisms or from dead microorganisms deposited over time (Vuillemin et al. 2023). Recent advances in molecular genetic methods have enabled the identification of past microbial communities, including prokaryotes, and the tracing of their evolution and adaptation to environmental changes (Eric Capo et al. 2021). This information is crucial for predicting future ecosystem shifts. The following studies showcase the type of information that can be obtained from microbial ancient eDNA and their interpretations.

5.5.1 Phytoplankton changes in response to climate in Polar ecosystems

Polar ecosystems are highly vulnerable to the ongoing climate change. The melting ice sheets and changes in oceanography in marine ecosystems are impacting all levels of the food web, especially primary producers. Changes in sea temperature and atmospheric CO2 levels are linked to shifts in the composition and size structure of phytoplankton communities, making them valuable palaeoindicators of climate change and ecosystem responses. However, some diatoms with heavily silicified structures preserve better than others, potentially skewing fossil analyses. This highlights the importance of sedaDNA techniques in complementing microfossil and other palaeo-proxy analyses for detailed investigations of periods undergoing environmental change, such as glacial-to-interglacial transitions.

Different studies have utilised sedimentary DNA from the Arctic and Antarctic environments to describe changes in phytoplankton communities, aiming to better understand the past and present responses of marine ecosystems to climate change. For example, a study by Buchwald and colleagues focused on the subarctic western Bering Sea, analysing metagenomic shotgun and diatom rbcL amplicon sequencing data over glacial–interglacial cycles, including the Eemian interglacial period (Buchwald et al. 2024). They identified distinct plankton communities during these periods: the Holocene was dominated by picosized cyanobacteria and bacteria-feeding protists, the Eemian featured eukaryotic picosized chlorophytes and Triparmaceae, and the glacial period had microsized phototrophic protists, including sea ice-associated diatoms and diatom-feeding crustaceous zooplankton. This long-term record revealed a decrease in phytoplankton cell size with rising temperatures, similar to current changes in the warming Bering Sea. These shifts suggest that future warming may increase productivity but reduce carbon export, weakening the Bering Sea’s role as a carbon sink.

On the other hand, Armbrecht and colleagues examined a sedimentary DNA record spanning ~1 million years from the Scotia Sea in Antarctica to understand changes in phytoplankton communities over time (Armbrecht et al. 2022) . They found records of diatom and chlorophyte sedaDNA dating back ~540 thousand years, reconstructing the oldest marine eukaryote sedaDNA record to date. When analysing the results, the authors concluded that warm phases were associated with high diatom abundance and a significant shift from sea-ice to open-ocean species around 14.5 thousand years ago, following Meltwater Pulse 1A.

Together, these studies illustrate the profound impact of climate change on marine ecosystems in both the Arctic and Antarctic regions and demonstrate the potential of sedaDNA tools to study long-term marine ecosystem shifts and palaeo-productivity across glacial-interglacial cycles.

5.5.2 Environmental microbiome associated with vegetational changes

In this study, researchers used shotgun metagenomics to analyse ancient eDNA from lake sediments in northern Siberia, aiming to understand ecosystem changes over the last 6700 years. They combined taxonomic and functional gene analysis to gain insights into how the genetic records of biological communities preserved in the sediment evolved over time. Additionally, they described changes in eco-physiological adaptations and ecosystem functions of microbial and vegetational communities in response to past climate variations.

The researchers found that 6700 years ago, the area was an open boreal forest, which gradually transitioned into tundra. The changes in the plant community reconstructed using sedimentary DNA matched perfectly with those described in previous studies using other palaeoecological proxies such as pollen, DNA metabarcoding, and hybridization capture (Schulte et al. 2021), further validating their observations. These shifts in palaeovegetation significantly impacted the environmental microbiome, with clear implications for ecosystem functioning. For example, there was an enrichment of certain bacteria and archaea that thrive in tundra conditions, particularly bacterial and archaeal ammonia oxidisers like Nitrospira, Nitrosopumilus, and Ca. Nitrosocosmicus.

This study demonstrated that microbial taxa, functions, and eco-physiological traits are valuable indicators of environmental conditions, highlighting their use as proxies in palaeoecosystem reconstruction.

5.6 Summary

Environmental DNA (eDNA) refers to genetic material shed by organisms into their surroundings, including water, soil, and sediments. It enables species identification without direct organism sampling, offering valuable insights into both current and historical ecosystems.

Environmental samples are inherently complex, containing a mix of genetic material from multiple species. This complexity is further amplified in ancient eDNA, where modern and degraded DNA are combined, making sample recovery and analysis more challenging.

The preservation of eDNA depends largely on environmental conditions. Cold, anoxic environments and clay-rich sediments help protect DNA for millennia. Taphonomic processes play a key role in the reliability of the DNA records.

Analysing ancient eDNA requires stringent laboratory protocols, with contamination control being critical during both field sampling and lab work to ensure the accuracy and integrity of the research.

Ancient eDNA provides a powerful tool for reconstructing past environments and tracking long-term ecological changes, such as climate-driven shifts in microbial, plant, and animal communities. This information is crucial for understanding ecological responses and guiding conservation efforts.